John J. Bullen, born Jan. 21, 1873, died May 9, 1974.

The high-back wicker chair creaked contentedly each time he shifted his weight despite there being very little weight to shift. The sound of Uncle Joe’s chair was familiar in the kitchen as was the impenetrable cloud of smoke which enveloped him from time to time. From his corner position he was able to survey all kitchen events, yet say little about the things he observed. Had it not been for the creaking chair or the distinctive odour of Sail pipe tobacco one could easily be oblivious to his daily presence. That was not the case regarding his presence in the family for Uncle Joe`s residency in St. Jacques coincided with the birth and raising of eight children under the roof of Tom and Burnsie Lawrence.

Despite arthritic hands whose knuckles twisted at odd angles, bent that way from years of immersion in winter waters off Bay de L`eau Island, his coordinated grasp of a tobacco pouch and a crooked stem pipe remained as agile as fifty years earlier. Holding the pouch in his left hand he would slowly position the pipe, use the forefinger of his right hand to rake tobacco towards the opening and stuff it into the bowl. Then, carefully he would fold the pouch, lay it aside and transfer the pipe to his left hand. Reaching into his pants pocket he’d rummage until he found a small pocket knife which would be improvised to tamp down the tobacco in preparation for lighting. Clutched in the palm of his hand was a box of Eddy Sure Strike wooden matches. In a single practiced twist of his wrist the match would strike the edge of the box and burst into flame. The same motion carried the match upward to hover above the pipe in his mouth, its flame then drawn downward with each intake of breath. He never used more than a single match to bring his pipe to full glow. After several puffs Uncle Joe was barely visible.

Soon his head, mottled with age spots and wisps of white hairs along the sides, would again be seen from across the room. The look of contentment on his face defied description as his aged frame, now as bent as his pipe stem, settled back into the wicker chair. Where he went when that pipe was under full steam I don`t know; however, I suspect he was at sea, again a young turk with sea legs braced, absorbing the ocean swell, watching the horizon for land, returning home to Bay de L’eau Island to the arms of Eliza and the memories of their two young children who never grew old.

John Joseph, is what his parents christened him. I suspect he was frequently called John Joseph by his mother and others living on Bay de L’eau Island as was the custom during the era in which he grew up. One can imagine listening and hearing boys being called for dinner: Randall Tom, George Sam, John Tom, Silas James and John Ben, with John Joseph standing among them, all preparing to scatter to various houses in the community just long enough to swallow a morsel of food and be off again to the exploits of young boys living on an island.

No one remembers Uncle Joe ever getting angry or upset. He quietly and politely engaged in conversation and offered his assistance to any outdoor activity taking place. He assisted with the sheep, the hens, mending fences and maintaining the property around him. Despite the gnarled knuckles, the bent back and the spindly legs, he remained active and mobile until he was one hundred. On civil weather days Uncle Joe could be seen making his way over Cellar Hill, Red Rail Hill and then to the bridge over Pittman`s Brook for a visit to Edgar Dyett`s General Store. His distinctive posture and walking cane was a fixture moving along that stretch of road for many years. Every time he received his Old Age Pension he would walk to the store and change it into cash where one of his first priorities was always to purchase some little item to give to the children. This token act was a way in which he could repay the kindness and generosity afforded him by the Lawrence family.

Uncle Joe came to St. Jacques in 1951 when Tom Lawrence moved there from Bay de L’eau Island. Bay de L’eau was being voluntarily resettled as were many of the other small communities throughout Fortune Bay. By then John Joseph Bullen was living alone, an elderly man of seventy-seven without any close relatives and no place to go. There was but one other household left on Bay de L’eau Island by that time and they too were preparing to relocate. The generosity, compassion and character that the people of St. Jacques came to know in Tom Lawrence explained his invitation to Uncle Joe to come live in his new house in his new community. Today, I marvel at the extremely human gesture that was extended that evening on Bay de`Leau Island. I try to imagine what it was like inside John Joseph Bullen`s mind when he realized the enormity of the offer. Knowing the principles and beliefs which guided Tom Lawrence throughout his life I`m certain that Matthew 25:40 wasn`t far from his mind , ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’

In addition to a love for tobacco, Uncle Joe had a penchant for Wrigley’s Spearmint chewing gum which then was marketed in packages of five sticks each. Between blissful episodes with his pipe he chewed gum. When he had chewed enough for an occasion he would stick it to his chair within easy reach for future chewing. A few short years before he died he took it upon himself to quit smoking which he was quite successful in doing; however, he probably chewed a little more gum.

He studiously rocked each child in the cradle there in the kitchen near where he usually sat until they fell fast asleep. He did this with the first child and each successive one as they came along. No doubt, this was a grateful act of an old man whose role as grandfather came not from his descendants but from the benevolent act of a neighbour who didn’t hesitate to make room for him to grow into that role.

His worldly possessions were minimal. When he left Bay de L’eau Island he took very little with him; when he left this world he left very little behind, memories, some old clothes, his beloved pipe and that now rickety wicker chair. He had saved enough money to cover his funeral expenses and bestow a small gift upon the family he had grown to love.

Joe Bullen was the first centenarian I ever knew. In fact, Uncle Joe had launched himself into his second century by the time he died. Despite having lost two children to illnesses before they reached the ages of twelve, he was never dogged by illness throughout his life. The first time he ever made a visit to a Doctor was when he fell and broke his arm at age ninety. He didn`t simply stumble and fall to the ground or across a piece of furniture as you might expect. Not Uncle Joe, he wandered in to the garage adjacent to the house where work was being carried out on a car. In order to work safely and comfortable underneath the vehicle an open Pit had been constructed into the floor of the garage approximately four feet deep. The Pit was usually covered by planks, however; on the day Uncle Joe visited, a car had just been removed from the garage leaving the pit temporarily exposed. Without noticing the opening he stepped directly into the abyss. Fortunately he broke only his arm and made a near-miraculous recovery with the arm healing in record time for someone his age.

When Uncle Joe celebrated his one hundredth birthday he was agile and alert. As the children assisted with placing one hundred candles on his birthday cake everyone gathered around had two thoughts in mind – will one hundred candles fit on the cake? And, will he be able to blow them out? As it turned out it took so long to light that many candles that the first to be lit were nearing the end of their fuel supply by the time the last were lit. The cake looked as though it had suddenly burst into flames and was being consumed right before everyone’s eyes. Uncle Joe who had smoked for most of his adult life took a deep breath, and with the gusto if a man determined to show his mettle, blew a breeze across that cake that rivaled any breeze which filled the mainsails of schooners heading out the Bay and left the cake sitting in a cloud of smoke! His was as delighted as every child in the kitchen that day.

He received a letter from the Prime Minister of Canada acknowledging his one hundredth birthday, but more impressive than that to him, was a similar letter from the Queen. In his lifetime the British Commonwealth had undergone tremendous change as had the circumstances of his own life, thus a letter from the Queen of England where, undoubtedly his grandfather had lived at one time, was as much mystifying as it was appreciated.

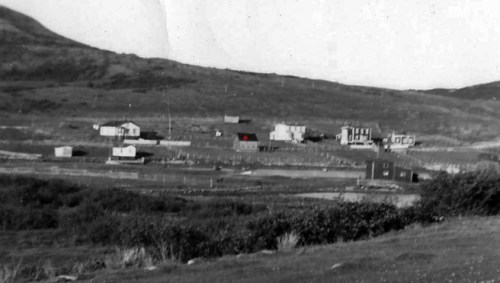

Resilience characterized the life of Uncle Joe Bullen. His life as a young man is not known to us in great detail anymore and the community in which he worked, married and sired children has dispersed and disappeared. However, the latter portion of his life was lived in the midst of a community where everyone knew and accepted him. For twenty-three years he looked out over St. Jacques Harbour, watched members of a new family grow into adults, enjoyed the comfort and care of an adoptive home, and witnessed phenomenal technological change – all at a stage of life that is well past the experience of many people.

1921 Census – Bay D`Leau

1935 Census – Bay D`Leau Island

World Events of 1873